Specialised language

Designing for people with autism, using specialised language, not 'owning' the words, and some AI label testing.

Here we are, back once again, not with the renegade master, alas, but a new edition of the Plain English Club newsletter. Sent by me, yep, Iain Broome.

I know four commas in the opening sentence of a newsletter about plain English is not ideal, but we are where we are. Thank you to everyone who shared the last email I sent you. Lots of new readers as a result. Hello new readers!

Without further faffing, on to the good stuff.

Iain

Use Specialised Language for Specialised Audiences

There is plenty in this Jakub Nielsen post from 2014 that applies today:

Even for specialised audiences it’s still best to write as simple as possible. Even highly educated people don’t want to struggle to read your site. You do not impress anybody by spouting highfalutin words or complex sentence structures that require careful parsing. People don’t pay close attention to web content.

He then goes on to make the case for using 'specialised language' if you are sure that the person reading knows what it means.

Specialised language is not only more concise but also clearer, as long as the reader is a specialist who understands the terminology.

I think this is still pretty good advice too. And I think the thrust of what he is saying is all wrapped up in the principles of what we now call content design. Effectively, before you write or design any content, make sure you understand who it is for and how they will use it.

That said, the one thing in the piece that I do strongly object to in this article is the bit about writing for specific 'reading ages'. Caroline Jarrett has covered this perfectly in her piece about reading age.

Do not use “reading age” when thinking about adults. It’s not helpful, and it fails to acknowledge the life experience of people with reading difficulties.

Don't forget you can find lots of other articles on this kind of thing in our shared list of Plain English Club Bookmarks!

From Shelter's style guide: Writing online content

Shelter is one of a handful of UK charities that do a two-toots tremendous job of publishing their approach to content on their website. I am a fan of this humble page on writing online content, which is concise and absolutely packed with useful, practical guidance for their content designers and writers to follow.

By the way, is it time to officially launch 'style guide of the week' as, you know, a thing?

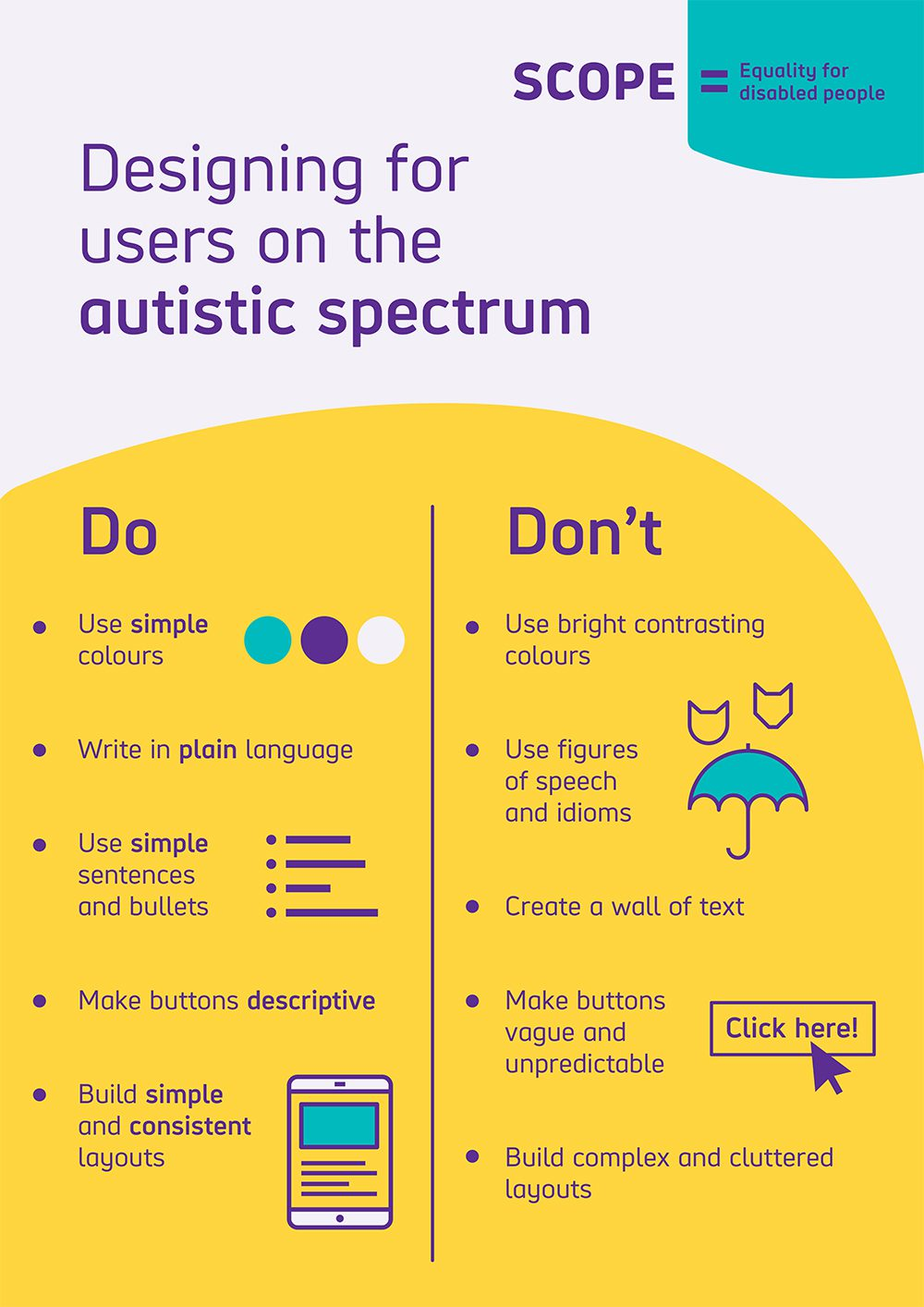

Designing for people on the autism spectrum

Another excellent resource from the frequently linked to (by me, especially) team at UK disability charity, Scope.

This isn't a bad place to start from with all your content:

It’s important to remember that how anyone chooses to talk about their impairment is up to them. If you’re referring to a particular person or group of people, always ask them how they would prefer to be described.

But if you specifically want or need to create content for people with autism, you'll find a list of useful, research-backed guidance. You can also swipe, print and share this handy infographic that covers the main points.

Content designers don’t ‘own’ the words. We never have

This post by Jane Van de Ban is pretty spot on about how misguided this notion is that content folk 'own the words'. I have previously used that phrase myself or perhaps, even worse, said that I or we 'own the style guide'. It's not really true though. Words and style guides are for everyone. Lucky people.

How we’re designing user-centred AI labels at the BBC

This is interesting insight into how the BBC are testing ways they disclose how AI has been used on their web pages:

AI labels have been appearing across all areas of tech, including social media, but we’re yet to see a consistent, transparent, truly user-focused and easily understood approach. That’s what we’ve been working on at the BBC. Over the past year, we’ve been developing a labelling approach that’s rooted in audience needs, designed to work across all our products, and focused on two main things: transparency and trust.

Some of the research findings so far are perhaps not surprising:

Throughout our research into AI labelling, audiences told us clearly that they don’t just want to know when AI is used, they want to understand how and why it is used.

There is lots here for you to get your teeth into and help you think about your own work. That said, I do find it a bit frustrating that there seems to be a working assumption here that audiences actually want AI at all.

The testing is being done on live sports pages. I follow live sports pages (especially cricket). The journalists who write that content are very good at it. They are funny, erudite and able to describe and convey the emotion and sense of community that comes with watching and enjoying live sport. It's a very human thing.

I dunno. I do try not be that guy when it comes to AI – I vibe coded the living daylights out of Bookmarks. But it does feel important for user research to ask, "Should we do this at all?" and not just, "We've done it. Do you trust us?"

"In the end, words on a page or in a service or in a print source don’t belong to any of us. They belong to our users - the people who need them in order to get their new passport, or book their train travel, or find out about the healthcare they need, or whatever it is they’ve come to our digital space to do. And our users don’t care who ‘owns the words’ - but they do care about getting things done."

Jane Van de Ban, Roxboro Design

New reader?

Join a growing community of almost 1000 clear language champs and start getting advice and resources that help you write clearer, more accessible content.